Sudoku Puzzle Introduction

Sudoku is an intriguing puzzle of patterns and cryptic rules. Regular Sudoku consists of a square grid to be filled in with numbers 1 to 9. The puzzle is to place these symbols in the correct place to complete the grid. Sudokus have been developed in many forms, they do need not be number based and can be letters or colors or shapes or whatever you like; it is a very varied type of puzzle.

There is just one simple rule controlling where you can place numbers in the regular Sudoku puzzle. A symbol must occur once and only once in each group of nine grid squares. The groups of nine squares include the rows, columns and regions within the puzzle. Such a simple rule leads to all the amazing range of Sudoku puzzles.

Take a look at our pages on the history of Sudoku, Sudoku solution strategy and theory.

Sudoku Terminology

First let's introduce the terms used on this web site, as not everyone uses the same convention. The whole puzzle area is called the grid, it is divided into rows (horizontal lines) and columns (vertical lines) made up of individual Sudoku squares.

Rows

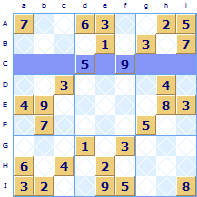

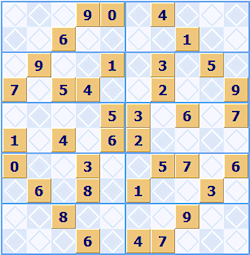

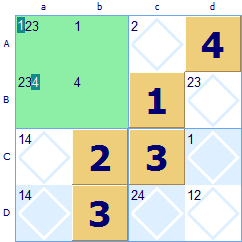

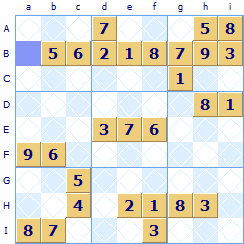

To save confusion we use letters rather than numbers to refer to rows and columns. The names are shown in the grid heading. In this Sudoku grid row C (capital C) is highlighted. Note: If we used numbers we would end up having to say things like in row 3 there is only one place for a 5 while in column 2 there are 3. Confusing isn't it? Using letters for grid references makes it easier to follow.

Columns

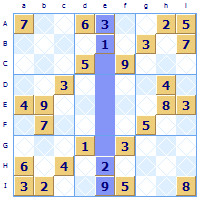

Sudoku columns are given a lower case letter.Column e (small e) is highlighted.

Using row and column letters lets us unambiguously refer to squares. For example square He is row H column e, this Sudoku square has a 2 allocated in the example puzzle.

Regions

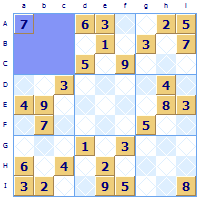

A region is a block of nine adjacent Sudoku squares, in the example puzzle the top left region Aa is highlighted. The whole grid is made up of nine regions. Some Sudoku sites use the term ‘mini-grid’; ‘box’ or ‘sub-grid’ for ‘region’. We think region is simpler and easier. A region is referenced by the top-left square, so region Dd is the central region. A symbol must occur once and once only in each of the regions within the grid as well as each row and column. This was one of the innovations that made Sudoku such an interesting puzzle to solve.Groups

A ‘group’ is a general term for a group of nine squares in either a row, a column or a region.

Rules

There is only one simple rule in Sudoku: each Sudoku group of squares must have a unique occurrence of each of the numbers 1 through 9.How to solve Sudoku puzzles

The process of solving a Sudoku puzzle is to fill in the empty squares. Each puzzle has a single, 'correct' solution, each unallocated square has one correct value from the 9 possible values.

Sometimes it is fairly obvious what number must go in a square while other squares require a great deal of mental torture to solve. To work through all the possibilities it can take half an hour to solve one square! Much like placing a single piece in a jigsaw, there must be a place for a number to go but spotting the correct place may be easy or take an age to do.

There is no correct sequence of square allocations to make, different people use their own strategies to solve a Sudoku puzzle and so will solve the squares in a different sequence. However, the end result is always the same, there is only one unique solution, just many ways of getting there.

There are a number of standard techniques or strategies to help solve a Sudoku puzzle. We have guides built into our Sudoku solver demonstrating these strategies. We also have a Sudoku strategy page containing a description of all the commonly used methods: only choice, only square, single possibility, excluded hidden twins, naked twins, sub-groups and X-Wing. The more Advanced strategies are explained on a separate page: X-Y Wing and Alternate Pairs. There is a page on Sudoku theory too.

You can visit our online discussion forums. Sudoku Dragon comes complete with guides that take you through the most useful solution strategies step by step.

Making mistakes

If you make an incorrect allocation of a number in a Sudoku puzzle then the puzzle becomes 'unsolvable'. At some later stage you will find an insurmountable contradiction, a number would have to be placed in two squares in the same row, column or region violating the Sudoku rule or else you'll find a square that can't take any of the numbers according to the rule. To correct the mistake you need to backtrack through the allocations that you have made until you find the one in error. Often this is because you overlooked another possibility for a square and thought it was the only choice.

Creating Puzzles

Skill is required to create a challenging Sudoku puzzle. It is not just a matter of randomly allocating numbers to squares. Firstly, to ensure that there is only one unique solution requires that there is the correct number of initial 'exposed' squares to begin with. If there were only a handful there would be many ways to allocate all the squares - but all Sudoku puzzles can have only a single, unique solution. The challenge is to reveal just enough squares to make the solution both unique and challenging. The pattern of squares can make a pleasing arrangement , and this should be taken into account when creating a Sudoku puzzle. In general the more revealed squares there are the easier the puzzle will be to solve. If the revealed squares are distributed evenly throughout the puzzle, then it will be easier to solve than if regions have very few filled squares. Some of the toughest puzzles have a couple of regions with no squares revealed at all, or when a particular number does not occur in the whole Sudoku puzzle. Solution strategies are discussed in our online forums and strategy page.

When Sudoku was published by the Nikoli magazine in Japan they decided to add some extra spice to form true Sudoku puzzles. They decided to make the pattern of revealed squares symmetric. If you turn the Sudoku on its side or upside down the pattern of initial squares is repeated (but not the numbers). Sudoku Dragon supports both a symmetric and a random pattern of initial squares. The random pattern can make the games more challenging to solve although it may be less aesthetically appealing to look at.

Sudoku Puzzle Difficulty

A good Sudoku puzzle has to have just the right level of difficulty. This decision is tricky because there are many solution strategies and different people will naturally find puzzles more challenging than others. The vital measure in establishing the level of puzzle difficulty is working out which Sudoku strategies are needed to solve it. The easier puzzles require the basic only square; single possibility and only choice rules. Moderate puzzles require some application of the twin and excluded choice rules. Truly challenging puzzles require the discovery of X-Wings, X-Y Wings, alternate pairs or may be even some use of trial and error: backtracking after following a blind alley or two before the correct solution is attained.

Sudoku and Jigsaws

The closest puzzle to compare to Sudoku is perhaps the humble jigsaw. There are similarities both in the way it works and the pleasure gained by solving it. In a jigsaw there are lots of pieces to fit in to a rectangular pattern, there is only one solution and each piece can only go in one place. Sudoku is also a matter of putting things in the right place. If you like doing jigsaws you'll enjoy Sudoku too.

To solve a jigsaw everyone will put the pieces together in different orders. Most people will hunt and separate the edge pieces and then join these up before tackling pieces with distinct markings and then join these up. When nearing the completion of a jigsaw, particularly with problem areas such as large expanses of clear blue sky, you may look out for pieces of a particular shape. There are different strategies to apply depending on the stage of completeness and that makes jigsaws interesting.

Sudoku is just the same, there are strategies to use at the different stages of solving the puzzle. Some of these can become a tough trial and error process just like a jigsaw.

The joy of successfully completing a jigsaw is akin to that of solving a Sudoku puzzle, when the final square has been filled in, the satisfaction of correct completion is like stepping back to enjoy the whole picture when the final piece has been placed in a jigsaw. Everything is in its proper place.

Sudoku puzzle types

Starting from the standard Sudoku rule there are many ways to create a range of different types of puzzle. First of all you can change the size of the grid. Using the regular 9x9 grid is just one option. The simpler 4x4 grid is useful for learning the basics of Sudoku and we use it for some of our guides. With 4x4 there are only four symbols and four regions to consider, and so 4x4 can never make a hard puzzle.

Stepping up to larger sizes a grid of 16x16 makes a real challenge, because there are now 16 squares with 16 possibilities for each square. With this size there are not enough digits so the letters 'A' through 'I' or 'hexadecimal' digits will do admirably instead. Sudoku Dragon supports puzzles of this size. The sudoku grid size can be arbitrarily increased further to 25x25 and 36x36 and so on, but 16x16 with a total of 256 squares to complete is surely challenging enough; after that the puzzle has too many possibilities to carry around in the average sized mind.

You can also use rectangular regions to make up the grid rather than squares. Sudoku Dragon supports seven rectangular grids including: 2x3 grid (about the most common rectangular size you will find) and the 4x5 (or 20x20) monster sized grid. Here's an example of 2x5 rectangles making up a 10x10 puzzle.

Our Theme and Variations page describes the many different types of Sudoku available. These include Chinese numbers; Word Sudoku; X Sudoku and Super-Sudokus or Samurai Sudoku with their overlapping 3x3 puzzles that have five overlapping puzzles to solve in one large puzzle.

How many possible puzzles?

As there are so many Sudokus printed these days, surely all the possible grids have now been solved? Well you may think so.

After a little thought it is clear there are quite a few new puzzles left and we are unlikely to run out of Sudokus in the near future. For each row in isolation there are 9! (shorthand for nine factorial) possible permutations of numbers for the squares which gives 362,880 possible orderings for just one row. Each of these rows can be combined with 8 other rows, and temporarily ignoring the Sudoku rule for columns there would be 9! to the power 9 which works out to be about 10 to the power 50 possible grids (that's 10 with 50 zeroes after it).

109,110,688, 415,571,316, 480,344,899, 355,894,085, 582,848,000, 000,000

Applying the Sudoku rule to columns as well as rows reduces this figure substantially. Just considering unique solutions for rows and columns and not regions means that the second row only 8 options to choose from for each square and 7 for the third etc. so this gives a much smaller number.

More grids can be knocked out if regions are taken into account as well as rows and columns. Fortunately some clever people have used super sized calculators to do the maths and claim there are 6,670,903,752,021,072,936,960 unique Sudoku grids of size 9x9. As this is roughly the number of stars in the observable universe, that is plenty to be getting on with.

But if you then start determining symmetries including rotations and swaps then the number of 'effectively different' puzzles goes down to 5,472,730,538. This large number means that is you solved one puzzle every second every day you would not need to repeat the same one in over a hundred years. These puzzles would all require different strategies to be used for their solution.

See: For more mathematical analysis ➚ and Some mathematical analysis into the actual number of possible puzzles ➚.

Solution Strategies

There are only a few strategies that you need to master in order to solve all Sudoku puzzles. Please also take a look at our Sudoku introduction page on terminology and also our theory page. You can share your tips and experiences on our strategy message forum. Here are the techniques you need for most puzzles, the most difficult ones however need advanced level strategies which are fully explained on our advanced page.

Only square Sudoku rule

Often you will find that within a group there is only one remaining place that can take a particular number. For example if a group has seven squares allocated with only two numbers left to allocate it is quite common that an intersecting (or shared) group forces a number to go in one of the squares and not the other one. You are left with an only square within a group for a number to go in. This is different to the 'single possibility' rule where we looked at individual squares rather than groups.

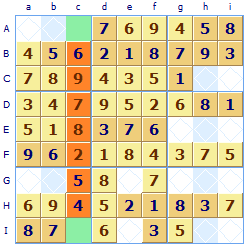

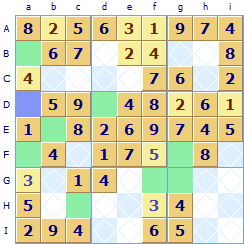

In this puzzle column c (highlighted) has seven numbers allocated. The missing numbers are 1 and 3. But you can see that there is already a 3 in row I (square If) so a 3 cannot go in square Ic, the 3 must go in the other square Ac it is the only square in column c where a 3 can be allocated.

In this puzzle column c (highlighted) has seven numbers allocated. The missing numbers are 1 and 3. But you can see that there is already a 3 in row I (square If) so a 3 cannot go in square Ic, the 3 must go in the other square Ac it is the only square in column c where a 3 can be allocated.

You will often find that the same square can be solved by the ‘single possibility’ rule as well as the ‘only square’ rule. It doesn't matter which rule you use, as long as the square is solved. Note: Whenever there are eight allocated in a group with only one remaining empty you can assign a symbol by applying either the 'only choice', 'single possibility' or 'only square' rules as all of them come down to the same thing. Sudoku allows squares to be solved in different ways using different strategies.

Two out of three strategy

This makes extensive use of the Only Square rule. Some Sudoku authors refer to it as ‘slicing and slotting’. It is a quick way of solving squares as it can be done in your head by scanning the puzzle grid. It almost always finds a square or two that can be solved. At the heart of the technique is to take groups of three rows and columns in turn, working methodically through the whole grid. First look for all the 1s then all the 2s, 3s etc. all the way through to the 9s. Here's an example of how it works, for more details look at our 2 out of 3 strategy page.

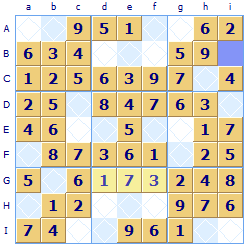

Look at the top three rows where the 1s are located - they are in row A column e (Ae) and Row C column a (Ca)

There is no 1 in row B, it must go in one of the blank squares. Because of the 1 in Ae it can not go in any other of the squares in region Ad that is Bd; Be or Bf. By elimination there is only one square a 1 can go in row B and that is in the highlighted square Bi.

Using the same logic for the following three rows D; E; F there is again two of them with a 1 in them: squares Eh and Ff. There is a 1 missing from row D and because of the 1 in Eh it can't be in Di, 1 must be assigned to Dc. For the last three rows there are already three 1s Gd; Hb and Ig so there is no 1 remaining to be allocated.

Look at the top three rows where the 1s are located - they are in row A column e (Ae) and Row C column a (Ca)

There is no 1 in row B, it must go in one of the blank squares. Because of the 1 in Ae it can not go in any other of the squares in region Ad that is Bd; Be or Bf. By elimination there is only one square a 1 can go in row B and that is in the highlighted square Bi.

Using the same logic for the following three rows D; E; F there is again two of them with a 1 in them: squares Eh and Ff. There is a 1 missing from row D and because of the 1 in Eh it can't be in Di, 1 must be assigned to Dc. For the last three rows there are already three 1s Gd; Hb and Ig so there is no 1 remaining to be allocated.

Now look at the 2s in these three sets of three rows. In rows A; B; C there are 2s in Ai and Cb so there is a 2 missing in row B, however in this case there are three unallocated squares Bd; Be and Bf so it can't be quickly decided in which one of these the 2 should go. The same happens in rows D; E; F there are two 2s but both Ed and Ef are possible. Finally in G; H; I there are two 2's Gg and Hc and so there is a 2 missing in row I. The existing 2's mean there is only one place it can go - square Id. You can then continue this scan through all rows then all columns in groups of three and then through all the numbers 1 through 9. Whenever you allocate a square this may unlock other squares so it is worth doing the whole procedure again over the whole grid.

see it in Sudoku Dragon click here...

The procedure is to scan rows and columns in groups of three and look to see where if anywhere the number being scanned has been allocated. If you find two out of the three then you know that the missing number can only go in only one of three squares in this row (or column), and more often than not only one of these is possible and must be allocated there. It will find squares that you could also have found using the only choice, only square and single possibility rules. The way it works is that three rows or columns consist of three regions each of these can only take the symbol once.

When using the Sudoku Dragon software you can use the automatic allocation feature to automatically highlight and solve squares that can be solved with the ‘only choice’, ‘single possibility’ and ‘only square’ rules, leaving you free to concentrate on solving the harder squares.

Sub-group exclusion Sudoku rule

More rarely needed in Sudoku, but exceptionally useful is the sub-group exclusion rule. This takes a lot more explanation as instead of 'forcing' a number in a square, it is an application of logic that knocks out options that at first sight looked possible. By excluding one possibility for a square may mean there is only one remaining possibility, so the square can be safely set to the remaining single possibility. Here's an example of the sub-group rule.

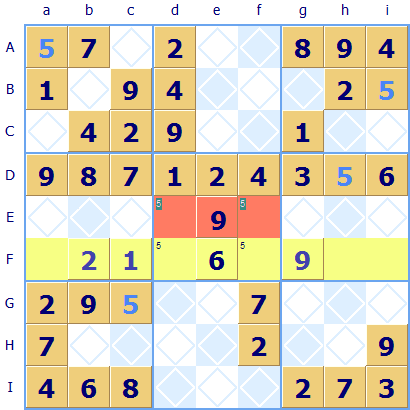

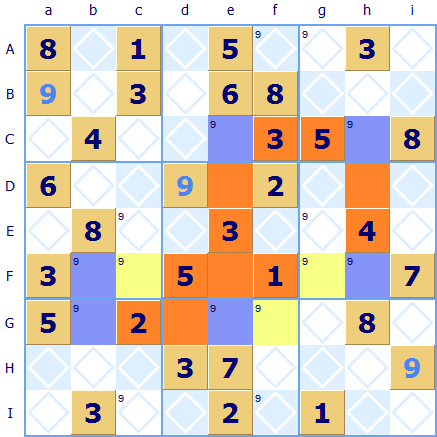

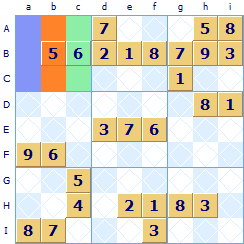

Scaling up to a regular 9x9 Sudoku example, subgroup exclusion can be applied to the central region Dd. It is the sub-group of the central region with the highlighted row F that is of interest. Look at the squares in row F that a 5 can go, it can't go in Fa (because of Aa) nor in Fh (because of Dh) nor in Fi (because of Bi). That only leaves Fd and Ff which form a shared sub-group with the central region Dd. The subgroup exclusion rule requires that a 5 can not go in the other unallocated squares in that region Dd highlighted in red: Ed or Ef.

Scaling up to a regular 9x9 Sudoku example, subgroup exclusion can be applied to the central region Dd. It is the sub-group of the central region with the highlighted row F that is of interest. Look at the squares in row F that a 5 can go, it can't go in Fa (because of Aa) nor in Fh (because of Dh) nor in Fi (because of Bi). That only leaves Fd and Ff which form a shared sub-group with the central region Dd. The subgroup exclusion rule requires that a 5 can not go in the other unallocated squares in that region Dd highlighted in red: Ed or Ef.

Hidden Twin exclusion Sudoku rule

The twin exclusion rules are useful for more challenging Sudoku puzzles. It is the strategy to use when simpler strategies have been tried and you are still stuck. In essence it is all about spotting matching patterns of possibilities in a group (row, column or region). Spotting these groups takes time and it is difficult to keep track of these in your head, so this is where you need pencil and paper. The rule applies equally well to groups of three, four or more squares but pairs are more commonly find.

If you have two or more unallocated squares in a region and there are two numbers that can only go in the same two squares and no others in that group then you have a twin. This does not directly help to allocate squares as the number could go in either of them. However, if the two squares have another possible number then this number can be safely eliminated as an option. It is excluded because of the presence of the hidden twin in the group. Studying an example is the best way to understand this rule.

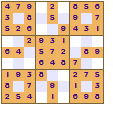

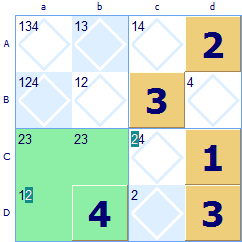

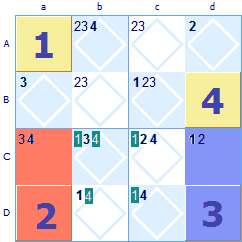

Look at this 4x4 grid. There are a lot of easier squares that could be filled in, but we've ignored them as we are illustrating the hidden twin rule. Look at the green region Aa, none of the squares have yet been allocated. Both 2 and 3 must go somewhere in the region but it turns out that there are only two possible squares. So we have detected a twin {2,3} in squares Aa and Ba. Because of this twin the possibility of a 1 in square Aa can be safely excluded (highlighted with white text on green).

Square Ba looked like it might be a 4 but this too can be excluded due to the same {2, 3} twin. How does this work? There are only two ways that the twin of {2, 3} can be allocated, either the 2 in Aa and 3 in Ba or alternatively 3 in Aa and 2 in Ba. These are the only two ways that {2, 3} can be set in this region. These are the only two possible ways that the squares Aa and Ba can be allocated. This does not allow the possibility of the 1 being allocated in Aa or the 4 being allocated in Ba - they must be allocated somewhere elsewhere in the group. Whenever there are the same number of possibilities restricted to the same number of squares this logic can be applied. [See the theory page for further explanation.] Note: The rule for twins extends to triplets too. If you find that three symbols have only three shared possible squares in a group (row, column or region) then all other possibilities in these three squares can be discounted. And on it goes, the same rule applies to quadruplets, quintuplets etc. but these are very rarely found in Sudoku puzzles.

Look at this 4x4 grid. There are a lot of easier squares that could be filled in, but we've ignored them as we are illustrating the hidden twin rule. Look at the green region Aa, none of the squares have yet been allocated. Both 2 and 3 must go somewhere in the region but it turns out that there are only two possible squares. So we have detected a twin {2,3} in squares Aa and Ba. Because of this twin the possibility of a 1 in square Aa can be safely excluded (highlighted with white text on green).

Square Ba looked like it might be a 4 but this too can be excluded due to the same {2, 3} twin. How does this work? There are only two ways that the twin of {2, 3} can be allocated, either the 2 in Aa and 3 in Ba or alternatively 3 in Aa and 2 in Ba. These are the only two ways that {2, 3} can be set in this region. These are the only two possible ways that the squares Aa and Ba can be allocated. This does not allow the possibility of the 1 being allocated in Aa or the 4 being allocated in Ba - they must be allocated somewhere elsewhere in the group. Whenever there are the same number of possibilities restricted to the same number of squares this logic can be applied. [See the theory page for further explanation.] Note: The rule for twins extends to triplets too. If you find that three symbols have only three shared possible squares in a group (row, column or region) then all other possibilities in these three squares can be discounted. And on it goes, the same rule applies to quadruplets, quintuplets etc. but these are very rarely found in Sudoku puzzles.

This rule is named the hidden twin rule as the twins are only found by considering other squares in the group. Discovering the twins is the challenge.

Naked Twin exclusion Sudoku rule

Another way to exclude possibilities in a group is with naked twins. In this case the twin squares are evident on their own (and this is why they are termed ‘naked’ rather than the previous ‘hidden’ case). They exclude possibilities in other squares in the same group. Here's how it works.

Another way to exclude possibilities in a group is with naked twins. In this case the twin squares are evident on their own (and this is why they are termed ‘naked’ rather than the previous ‘hidden’ case). They exclude possibilities in other squares in the same group. Here's how it works.

This 4x4 Sudoku has the region Ca highlighted in green. The ‘naked twins’ are located in Ca and Cb with possibilities {2, 3}. Because these two squares have no other possibilities we can deduce that a 2 must go in Ca and 3 in Cb or else 3 in Ca and 2 in Cb, there are no other alternatives for these two squares. So looking at square Da the naked twin rule excludes 2 from occurring here (because we have just shown that region Ca must have a 2 in either Ca or Cb). As Da is now left with a single possibility, a 1 can be safely allocated there. Looking at row C which also contains the naked twin, the rule eliminates 2 from square Cc and a 4 must go there.

Chain permutation Sudoku rule

The two twin rules are examples of a more general logic. It is all down to permutations - explained in detail on our theory page. Each Sudoku group is a permutation of the numbers 1 to 9 (for a 9x9 grid). If you can identify a group within this permutation that is restricted to the same number of squares then you have a Sudoku permutation rule. In fact the ‘only square’; ‘single possibility’ and ‘only choice’ are just special cases of this general rule - only one square is involved in this case. This general rule has more exotic applications.

The twin, triplet, quadruplet rules just reflect different number of possibilities (2, 3, 4...). However there are also chains. A chain can take in any number of squares, for example if three squares in a group allow just the possibilities {1, 7}; {4, 7} and {1, 4} there is a closed chain of three symbols {1, 4, 7} which is neither a twin nor a triplet. Detecting this chain lets you safely exclude a possible 1, 4 and 7 elsewhere in the same group. So the logic applies equally for chains as it does for twins, there are 'naked chains' and 'hidden chains'.

X-Wing and Swordfish

One of the more complex Sudoku strategies is the ‘X-Wing’ and its cousin the ‘Swordfish’. These rules are needed in really difficult Sudoku puzzles when all else has been tried and failed.

In looking for twins and permutations we restricted ourselves to looking at possibilities within a single group. The shared sub-group rule is the simplest example of a rule where two groups are looked at to eliminate possibilities. The X-Wing also requires looking at more than one group. A better name for this strategy might be ‘Box’ as you are looking for four squares forming the corners of a box. These squares must be the only permitted squares for that number in that row (or column) for one particular symbol. This box arrangement forms a two dimensional link. If the symbol spotted occurs in the top left corner of the box it must then also occur in the bottom right corner of the box. The only other alternative is that it occurs in the top right corner in which case it must then occur in the bottom left corner. No other option is possible for these four squares and this number. Just as with the sub-group rule, this can knock out possibilities somewhere else in the Sudoku puzzle.

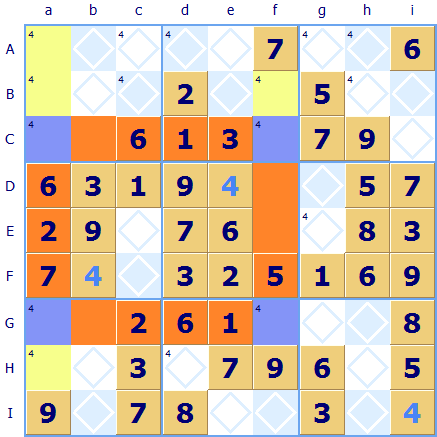

Here's an example (and good X-Wings are hard to find). Sudoku Dragon has highlighted all the squares where a 4 is allocated or looks like it can be allocated. The rows C and G are crucial. They both have only two squares that can take a 4: Ca, Cf, Ga and Gf - highlighted in blue - this is the vital starting point. Moreover these 4s form the corners of a rectangular box (highlighted in blue). How is this useful? Well, because there must the 4 in column a must either go in Ca or Ga and nowhere else in that column. Similarly in column f (the 4 must be in either Cf or Gf and so we can exclude all the other 4s from these two columns. So all the yellow highlighted squares Aa, Ba, Bf and Ha can have the possibility of 4 safely discounted. If you are lucky then eliminating the 4s will mean you can allocate one of these excluded squares. Note: The term X-Wing is probably derived from the name of the Star Wars fighter ➚ which had an X shaped cross-section.

see it in Sudoku Dragon click here...

Believe it or not the complexity does not end at the X-Wing, the Swordfish is a further refinement of the X-Wing. Instead of four squares forming a box of possible allocations the Swordfish rule uses six squares. In the example puzzle there are not just two pairs of squares for 9 but three pairs: in columns b; e and h. These squares are highlighted in blue/purple color. They are linked by rows to form a box with an extension 'sword' jutting out on one side : hence the term Swordfish ➚. The other squares forming the swordfish are highlighted in orange and yellow. Because all these three columns have coinciding end squares the rule applies again. Any 9s that we find in rows that link the columns can be safely excluded because we know that a 9 must occur in one of the two highlighted squares in that row; they can't be allocated elsewhere. These excluded squares are highlighted in yellow (Fc; Gf and Fg).

Believe it or not the complexity does not end at the X-Wing, the Swordfish is a further refinement of the X-Wing. Instead of four squares forming a box of possible allocations the Swordfish rule uses six squares. In the example puzzle there are not just two pairs of squares for 9 but three pairs: in columns b; e and h. These squares are highlighted in blue/purple color. They are linked by rows to form a box with an extension 'sword' jutting out on one side : hence the term Swordfish ➚. The other squares forming the swordfish are highlighted in orange and yellow. Because all these three columns have coinciding end squares the rule applies again. Any 9s that we find in rows that link the columns can be safely excluded because we know that a 9 must occur in one of the two highlighted squares in that row; they can't be allocated elsewhere. These excluded squares are highlighted in yellow (Fc; Gf and Fg).

Of course, the Swordfish is not the end of the matter we can extend the logic to four interlinking pairs of possibilities and then five etc.. You'll feel a real sense of achievement if you locate a Swordfish and use it to solve a Sudoku puzzle.

see it in Sudoku Dragon click here...

More advanced strategies

Further complex strategies are available for fiendishly difficult puzzles. They require a lot more thought and analysis to learn about and use correctly. The techniques include the X-Y Wing or Hook and powerful Alternate Pair , they are explained in full on our separate Advanced Strategy page.

Backtracking or solving by Trial and Error

When all else fails, there is one technique that is guaranteed to always work, indeed you can solve any Sudoku puzzle just using just this one strategy alone. You just work logically through trying each possible alternative in turn for every square until you find the solution. If you choose a wrong option at some stage later you will find a logical inconsistency and have to go back, undoing all allocations and then trying another option. Because there are so many alternatives (billions) you won't want to use this technique too often. You start with a square and choose one number from the available possibilities. This is a completely different type of strategy as it uses brute force rather than logic. Many believe this is not really a proper Sudoku solving technique as no real skill is involved. We have a full description of it with examples on a separate Guessing page.

Copyright © 2005-2025 Sudoku Dragon

Looking at the second row (B) all the squares except the first one Ba have been allocated so the missing number 4 has no choice but to go in the square

Looking at the second row (B) all the squares except the first one Ba have been allocated so the missing number 4 has no choice but to go in the square  In this partially solved Sudoku there are quite a few readily solvable squares. Look at the purple square

In this partially solved Sudoku there are quite a few readily solvable squares. Look at the purple square

Here is a brief example using the

Here is a brief example using the